Reactive is one of the buzzwords of our time. Since one thread per request is so 90s and so all our beloved microservices have to be reactive, that is responsive, elastic, resilient, and message-driven - whatever that means. Moreover, we understand that modern applications need to deliver information in realtime. Batch processing is so 80s and so all our beloved microservices have to process data as soon as it arrives and forward the new intermediate results to other microservices as soon as possible. But an upstream service might be faster than its downstream services, and memory is limited, so the upstream might have to slow down so that the downstream does not get overwhelmed. The heroic software engineer understood the problem and sallies to build their own library to solve it. But reinventing the wheel over and over again is so 70s. Luckily, many smart people sat together to outline a common framework for reactive streams on the JVM.

The idea behind reactive streams

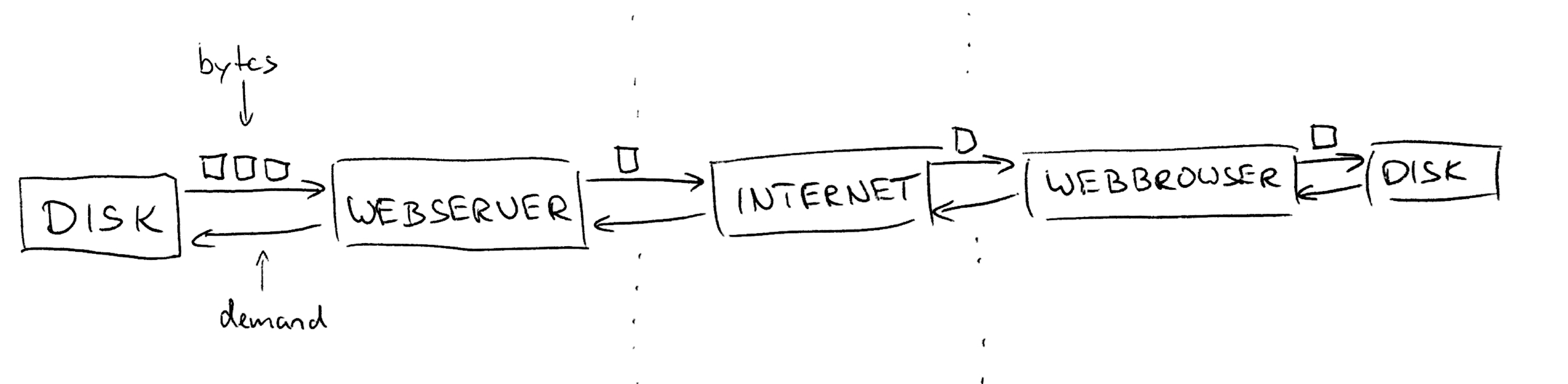

What is a stream? A stream shares many traits with an ordinary collection. For example, both, a stream and a collection, define a certain order on their elements. Starting with the first, then the second and so on. But as a collection can be picked up as a whole, a stream has a temporal component. Even though one might have a stream at hand, the individual elements in that stream might not yet be available. And other elements might already have passed away. A reactive stream is also just a stream but with another addition, the so-called “back-pressure”. Back-pressure means, that the upstream part of a stream only produces data when the downstream part signaled its readiness. This concept is really not new. A classic example for a back-pressured stream is a simple file download.

The web server will send you one chunk of bytes after the other. But at any given time the server will only have loaded as much data from disk into memory as you as a client are capable of retrieving. How fast you can download the data depends on the speed of your internet (which will most likely be the slowest link in the chain). But if you have 10GB network, then it might be faster and your web browser might be the bottleneck due to CPU limitations. And if the CPU is also fast enough, then your good old magnetic hard drive will be the bottleneck.

Let’s assume the hard drive is the bottleneck. If every other stage in the chain keeps running as fast as it can, then data will pile up in your web browser. Eventually your memory is filled up and the browser only has two bad options: Drop byte chunks or completely cancel the download. I guess you never had a download canceled, because the web server was too fast. Maybe because you never had internet that is faster than your disk drive. But even if: Back-pressure prevents this kind of problems. No matter which is the slowest stage in a reactive streams chain, the other stages will slow down accordingly, so that every individual stage can catch up and does not have to cache extraneous data elements which have already flowed in, but cannot yet be processed.

The back-pressure is archived by a simple twist: Every stage keeps a demand counter that is initially 0. Only if the downstream demand is positive it is allowed to send elements downstream. To stay in our picture of the download: The first thing that happens is the client’s disks signaling demand, saying it is ready to store data. This demand is propagated upstream to the web browser and from there over the internet and so on. When the demand hits the server’s disk, data is read and sent downstream to the web server and from there over the internet and so on. If one stage slows down, the whole downstream-data/upstream-demand cycle slows down.

Coding example with akka-streams

The reactive-streams API is not intended for direct usage, but as an interop-layer between individual frameworks. A non-exhaustive unordered list is

and many more.

Let’s take a quick look at how our example would look like with Akka streams.

Before we need some wording (just ignore the type parameter M for this blog post):

Source[Out, M]: In Akka streams a source is a stream stage that only has a downstream side. So basically it creates elements out of thin air. For example by an algorithm or by reading data from a disk (the data from the disk is not thin air, but from an API point of view there is no further upstream stage).Flow[In, Out, M]: A flow is a stream stage that has an upstream and a downstream side. So elements flow in are processed and then passed downstream.Sink[In, M]: A sink is a stream stage that only has an upstream side. So it has elements flowing in but nothing flowing out. This could be console logging or writing to disk.

Here is the example code:

import java.nio.file.Paths

import akka.NotUsed

import akka.actor.ActorSystem

import akka.http.scaladsl.Http

import akka.http.scaladsl.model.{HttpMethods, HttpRequest, HttpResponse}

import akka.stream.scaladsl.{FileIO, Flow, Sink, Source}

import akka.stream.{ActorMaterializer, ThrottleMode}

import akka.util.ByteString

import scala.concurrent.Future

import scala.concurrent.duration._

object AkkaStreamsExample {

implicit val system = ActorSystem()

implicit val materializer = ActorMaterializer()

// a future on the http

val httpResponse: Future[HttpResponse] = Http().singleRequest(HttpRequest(HttpMethods.GET, "http://my.domain.com/file.tar.gz"))

// convert the future into a source that emits a single element (the response)

val httpResponseSource: Source[Source[ByteString, Any], NotUsed] = Source.fromFuture(httpResponse.map(_.entity.dataBytes))

// convert the single response source into a source of the response body byte chunks

val httpResponseBodySource: Source[ByteString, NotUsed] = httpResponseSource.flatMapConcat(identity)

val clientWebbrowser: Flow[ByteString, ByteString, NotUsed] =

Flow[ByteString]

.map { chunk =>

println(s"Received ${chunk.length} bytes")

// browser does nothing, just passes down bytes chunk unaltered

chunk

}

val clientDisk: Sink[ByteString, NotUsed] =

Flow[ByteString]

// throttle to at most 3 byte chunks per second to simulate a slow disk

// to throttle down to a certain bytes/second speed, we would have to also incorporate

// the length of every byte chunk, not only the chunk count

.throttle(3, 1.second, 3, ThrottleMode.shaping)

// all inbound byte chunks get written to disk

.to(FileIO.toPath(Paths.get("/path/to/target/file")))

// download the file

httpResponseBodySource.via(clientWebbrowser).to(clientDisk).run()

}Beautiful, isn’t it?

And it is light on used resources.

We artificially made it very slow.

Most of the time it is waiting because of the throttling.

Still there is no thread bound to all of this.

Only when there is really work to do, for example, the println part, then we use processing resources.

If we do not get new byte chunks no thread will be blocked.

So the resources are free to be used somewhere else.

Are you even using this?

Yes we are. Even though it is only a single service. Our new storage service responsible for storing binary files and images is completely written with Akka, Akka streams and Akka HTTP. In addition to simple disk storage it acts as a proxy to our old image storage and enriches it with better image manipulation functions. Here we really benefit from the reactive streams, when we stream data from the old image storage, process it, and forward it to the client. And who knows, maybe in the future there will be more Akka love in our house.