Whether you love it or hate it, you can hardly ignore React and its ecosystem nowadays. React is (just) JavaScript (if you strip away JSX & friends), and not everyone has (or is willing to have) a JavaScript background. Unfortunately, there are some further obstacles on the road to an efficient universal React app. When you finally decide on building your frontend with React, you still need some backend that is delivering the initial page. That’s where it gets tricky.

You want to render your first page view on the server (for SEO reasons), and afterwards continue navigation as an SPA on the client. This means that you need some kind of synchronization between your client-side routes and your server-side routes. Of course you only want to define them once. As you only want to write your views once too, you probably end up designing the backend for your frontend (BFF) as some kind of Node.js app, since that’s the only way to render (and route) your React components. Although Node.js lets you create apps and APIs pretty fast and straightforward, it lacks concurrency, and proper failover strategies out of the box. Moreover, the NPM ecosystem hasn’t had the best reputation recently. Let’s say we want to create a more resilient backend and use Elixir as an example implementation. This leaves us with a couple of challenges for our undertaking to be solved.

- Have one place to define our routes used by client and server.

- Render our react components on client and server.

- Use something else than Node.js on the backend (also because it would be too easy otherwise).

There’s some stuff to do. So let’s go to work, shall we?

Forging the resilient backend

Before we can go and implement our shiny React app, we need someone to deliver the inital HTML page including the script tags. This will allow React to do its magic on the frontend. In the first step we will create a lean HTTP server using Plug, a specification and conveniences for composable modules between web applications. We want it to do the following things:

- Deliver static assets to the frontend (e.g. a webpack js bundle).

- Render a static html template with a script tag loading the bundle.

- Bonus: Split requests between view rendering and API (for demonstration and for later).

defmodule My.Router do

use Plug.Router

plug Plug.Static,

at: "/static",

from: "priv/static"

plug :match

plug :dispatch

forward "/api", to: Luke.ApiRouter

forward "/", to: Luke.ReactRouter

end

Let’s break down the above building blocks (plugs).

Plug.Static is used to serve everything in the priv/static directory under /static to the client.

The two plugs :match and :dispatch are needed to match routes, and invoke the appropriate handler (plug) via the forward functions right underneath.

That’s it, our router is ready to accept requests.

However, before we can respond, we need to create the two mentioned sub-routers (we forward to) for handling API and view requests.

For our API router we only do a dummy implementation.

defmodule My.ApiRouter do

use Plug.Router

plug :match

plug :dispatch

match _ do

send_resp conn, 501, "Not implemented"

end

end

Each request arriving on /api gets forwarded to that router and will therefore be confirmed with a friendly 501.

The frontend (React) router will do something quite similar but with two differences.

Instead of a generic match we are only interested in get requests and, friendly as we are, we’re going to render a real nice template with status 200.

Using Embedded Elixir (EEx) templates we create a small Render module that can magically create a template function from file.

defmodule My.Render do

require EEx

EEx.function_from_file(:def, :index, "index.html.eex", [:html])

end

This gives us an index function that receives an html parameter which is then injected in the template.

Besides the usual HTML tags we will also be including a script tag to load our React app later.

Speaking of which… now would be a good time to write that one.

Creating a simple React (frontend) app using react-router

We’ll be using react-router v4 for client-side routing. It comes with components that let you declaratively define your routes in JS(X). Since I wanted to keep the boilerplate small, I decided to write the frontend part in vanilla JS. Consider the following setup:

const { createElement: h } = require('react')

const { Route, Switch } = require('react-router')

const App = () => {

return h(

Switch,

null,

h(Route, { exact: true, path: '/', component: Home }),

h(Route, { path: '/a', component: A }),

h(Route, { path: '/b', component: B }),

h(Route, { component: NotFound })

)

}

This defines four routes.

Three of them render normal views while one (NotFound) serves as a 404 page.

With webpack or the likes we’re able to create the bundle which we put into our template delivered by the server.

Given components A and B have some react-router Links to jump around we already have an SPA with client-side routing.

Now we’re using the exact same app (with its routing) and render on the server.

Prepare for some awesomeness.

JSON is your new best friend

Michael Jackson (the react guy, not the pop guy) created a little project called react-stdio.

It lets you render react components by passing the path to the component together with a props object via STDIN, and get back the rendered output through STDOUT.

This lets you use React with every language that can spawn processes and communicate through standard streams with a JSON protocol.

Luckily, Roman Chvanikov wrote a great article on the refactoring of std_json_io, a convenient library for communicating with an external script.

Via JSON.

This is no coincidence since std_json_io was originally written for react-stdio.

While this was enough to render simple components it was a bit tricky to actually do routing.

Besides returning the output stream you also have to somehow inform the server about the result of react-router’s matching.

After some fiddling around and a PR that Michael merged, react-stdio now also returns a context for exactly that (and other abuses).

Heading back to our Elixir implementation of the React router.

defmodule My.ReactRouter do

...

case StdJsonIo.json_call(%{

"component" => "web/react-router.js",

"props" => %{

"location" => conn.request_path

}

}) do

{:ok, %{"html" => html, "context" => context}} ->

send_resp(conn, context["status"] || 200, My.Render.index(html))

{:error, %{"message" => message}} ->

send_resp(conn, 500, Render.index(message))

{:error, error} ->

send_resp(conn, 500, Render.index(error))

end

...

end

Instead of just returning our template we’re going to return the rendered match of our routing definition.

For a react-router to be working correctly we only need one prop.

The current request path.

We’re telling StdJsonIo to render our entry point JavaScript (see below), and pass the current location (the request path we got as a prop):

const { createElement: h } = require('react')

const { StaticRouter } = require('react-router')

const App = require('./static/App.js')

const context = {}

const Router = ({ location }) => h(StaticRouter, { location, context }, h(App))

Router.context = context

module.exports = Router

Notice that context is passed to the StaticRouter and exposed via the exported Router.

This is key for making the correct status code available to the calling Elixir plug (ReactRouter) and set it in the response.

Since the ReactRouter plug will assume a status code of 200 until told otherwise, we only have to set it in case of something going wrong.

Remember our NotFound component that is rendered when no route matches?

Here is what it actually does:

const NotFound = ({ staticContext }) => {

staticContext.status = 404

return h('h3', null, 'Sorry, we took a wrong turn.')

}

It populates the context with a status code (that is not 200) which is handled (and exposed) by the StaticRouter.

Ignoring the various error cases (timeout, syntax, …) that are handled by our above ReactRouter plug we can see a patternmatch for the actual content (html) and our context.

We can use this to send the appropriate response to the client:

...

{:ok, %{"html" => html, "context" => context}} ->

send_resp(conn, context["status"] || 200, Render.index(html))

...

What have we done

Every (GET) request (that is not /api/*) is forwarded to our react_router.ex plug.

Here we’re rendering our react-router.js entrypoint which uses the same app as the frontend.

StdJsonIo takes care of serialising and deserialising our JSON communication with react-stdio.

We can then render our EEx template with the delivered render output, and set the response’s status according to the react-router’s matching result (via context).

Besides having had a lot of fun experimenting there are some advantages over using a Node.js app.

With the external renderer script we can prevent the whole server from crashing when rendering 3rd party generated content on the server (3rd party themes in our special case).

But there’s more.

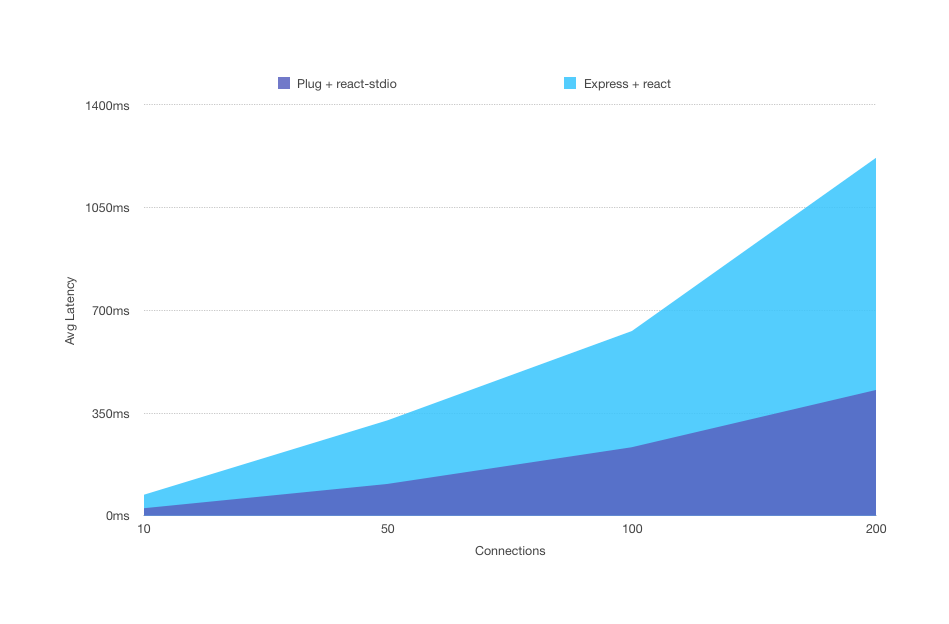

I did a little (naive) benchmark with wrk.

Check the latency (render timings) for different numbers of open connections:

The test was run with wrk -c {10,50,100,200} -d 30s http://127.0.0.1 on a MacBook Pro 2016 (i7 2.6GHz, 16GB RAM).

In contrast to the single-threaded Node.js server, our Plug-based server can create a pool of render processes:

config :std_json_io,

pool_size: 2,

pool_max_overflow: 4,

script: "node_modules/.bin/react-stdio"

Together with all the nifty little things from the BEAM and the elixir/erlang ecosystem I’m sure there’s some interesting possibilities to explore.

You can find the complete code on Github together with links to all the resources mentioned here.