After having explained how we use Multitenancy and Elasticsearch, we will continue our series of search-related blog posts by looking at a software architecture pattern called Command and Query Responsibility Segregation (CQRS) and how we embrace it for managing and accessing product data in our ePages shops.

Different product data models

In our ePages software we identified two fundamentally different usage scenarios when dealing with product data, each coming with its own data model.

The write model

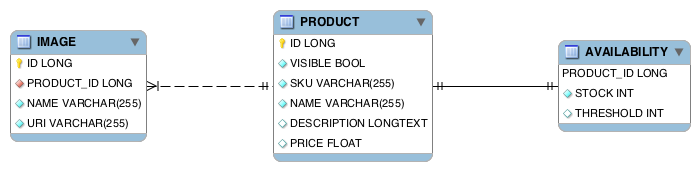

A merchant uses the administration area to manage all aspects of their shop, in particular it’s product data. This product data is stored in a relational database (RDBMS), where transactions and database constraints guarantee consistency and integrity. A simplified relational data model looks like this:

The read model

The storefront application renders product data for the customers visiting a merchant’s shop. It displays a list of products as a result of a customer browsing a category or using the search functionality of the shop. When navigating to a product detail page, more product-related data is presented to the customer.

Especially the need for full-text searching and faceted filtering (also called after-search navigation), influenced the choice to use search technology, namely Elasticsearch, as the only source for accessing product data from the storefront. A simplified JSON document of a particular product to be indexed by Elasticsearch looks like this:

{

"sku" : "334163-2",

"name" : "Sneakers",

"description" : "best running experience",

"price" : 49.99,

"availability" : "IN_STOCK",

"images" : [{

"name" : "front",

"uri" : "https://myshop.com/images/334163-2/front.jpg"

}, {

"name" : "back",

"uri" : "https://myshop.com/images/334163-2/back.jpg"

}]

}The availability state is a computed value based on the stock and threshold numbers.

This full set of attributes is only used when rendering the product detail page. Lists of products only show a subset of these attributes, hiding sku, description and all but one image.

Command and Query Responsibility Segregation

Having different models and services for mutating and querying data from the same business domain can be architected using CQRS.

We use a heavily normalized model for updating product data, what is called the Command Responsibility.

Our service for this use case is named product-management and uses a relational database for persistence.

The Query Responsibility in our scenario uses a denormalized model in a read-only fashion.

It is persisted using Elasticsearch and implemented in a service called product-view.

By segregating these responsibilites into specialized microservices, we can use the best fitting technology available for implementing them and also scale them asymmetrically. This takes into account that many more customers browse the different storefronts concurrently, compared to the number of merchants updating their product data.

Data synchronization

Whenever a product is created, updated or deleted in the database, we need to keep the Elasticsearch index in sync accordingly. In our microservices architecture, we use asynchronous messaging over an event bus to achieve this. While many CQRS implementations also use an architecture pattern called Event Sourcing, this is not what we based our message communication on. Instead product-management publishes events for different mutations of the underlying entities, which are consumed by product-view:

| Product-related events | Image-related events | Availability-related events |

|---|---|---|

| product-created-event | image-created-event | |

| product-updated-event | availability-updated-event | |

| product-deleted-event | image-deleted-event |

These events carry only parts of the full product data as JSON payload, based on the relational entity they are derived from:

Product event

{

"message" : "product-updated-event",

"payload" : {

"id" : 456,

"visible" : true,

"sku" : "334163-2",

"name" : "Sneakers",

"description" : "best running experience",

"price" : 49.99

}

}Image event

{

"message" : "image-created-event",

"payload" : {

"id" : 789,

"product_id" : 456,

"name" : "front",

"uri" : "https://myshop.com/images/334163-2/front.jpg"

}

}Availability event

{

"message" : "availability-updated-event",

"payload" : {

"product_id" : 456,

"stock" : 2,

"threshold" : 5

}

}Partial updates of documents

Updating an already indexed complete document in Elasticsearch is pretty straight forward:

PUT /products_12345/product/456

{

"sku" : "334163-2",

"name" : "Sneakers",

"description" : "best running experience",

"price" : 49.99,

"availability" : "LOW_STOCK",

"images" : [{

"name" : "front",

"uri" : "https://myshop.com/images/334163-2/front.jpg"

}, {

"name" : "back",

"uri" : "https://myshop.com/images/334163-2/back.jpg"

}]

}But when the update is triggered by one of the aforementioned events, we need to be a bit more careful: When processing an availability-updated-event, just computing the new availability state and including it as the only attribute in the update would wipe out all the other attributes of this product!

PUT /products_12345/product/456

{

"availability" : "LOW_STOCK"

}

GET /products_12345/product/456

{

"_index" : "products_12345",

"_type" : "product",

"_id" : "456",

"_version" : 2,

"found" : true,

"_source" : {

"availability" : "LOW_STOCK",

}

}Luckily, Elasticsearch offers a feature called partial updates to mitigate exactly this problem, leaving all remaining attributes untouched:

POST /products_12345/product/456/_update

{

"doc" : {

"availability" : "LOW_STOCK"

}

}

GET /products_12345/product/456

{

"_index" : "products_12345",

"_type" : "product",

"_id" : "456",

"_version" : 2,

"found" : true,

"_source" : {

"sku" : "334163-2",

"name" : "Sneakers",

"description" : "best running experience",

"price" : 49.99,

"availability" : "LOW_STOCK",

"images" : [{

"name" : "front",

"uri" : "https://myshop.com/images/334163-2/front.jpg"

}, {

"name" : "back",

"uri" : "https://myshop.com/images/334163-2/back.jpg"

}]

}

}Conclusion

Keeping decentrally managed data in sync is not trivial. Even when accepting Eventual Constistency, you need to implement data synchronization processes and take care of storage-specific peculiarities.

Asynchronous processing of events imposes another complexity by having no guarantees on the order of received messages. Introducing Elasticsearch optimistic concurrency control and retrying out-of-order events could minimize this, at the cost of yet another complex implementation detail.

The advantages of solving all these challenges must justify the effort involved. In our microservices architecture we already rely on messaging for data synchronization, so there is no additional complexity introduced. Giving us the option to scale product-view individually from product-management is only a minor benefit, but nevertheless nice to have.

By separating these two microservices, each of them can focus on its special technology stack, keeping the amount of knowledge needed to maintain each of them at minimum. Having all the safety of a relational database for manipulating product data as well as offering features mandatory for every e-commerce site by using Elasticsearch, is the biggest benefit.